Here’s a story I began reading more than a year ago and was initially fond of, but as is often the case with ZudaComics.com and my consistently under-performing home Internet speed thanks to AT&T, convenience drove me away until my pal Rickey Purdin dropped me a hard copy. I really love a lot of the content on Zuda, and the quality of work that DC’s system there produces consistently impresses me. The issue occurs, however, because Zuda’s strips are formatted in a way that requires me to blow them up to full screen size to read them, but when I do this, each page takes 40-50 seconds or more to load, and when you mix in two-panel and one-page splashes, this means it can take two or three minutes just to read a couple of short sentences worth of script. It’s consistently been a roadblock for me getting into a lot of their comics, since they shoot for long-form stories that can be handily collected. The simple truth is that if I can read 24 pages of a comic book in 5 minutes, 4-6 months of non-Flash interface webcomics in 10 minutes or 30 1-5-panel pages in a half hour, I’m almost always going to to go with the first two options. It boils down to simple time and math, as well as the annoyance I feel spending more time watching the word balloon icon load (he’s basically the Microsoft Word paper-clip of the webcomics reading experience for me) than reading comics, which is what I want to do.

Here’s a story I began reading more than a year ago and was initially fond of, but as is often the case with ZudaComics.com and my consistently under-performing home Internet speed thanks to AT&T, convenience drove me away until my pal Rickey Purdin dropped me a hard copy. I really love a lot of the content on Zuda, and the quality of work that DC’s system there produces consistently impresses me. The issue occurs, however, because Zuda’s strips are formatted in a way that requires me to blow them up to full screen size to read them, but when I do this, each page takes 40-50 seconds or more to load, and when you mix in two-panel and one-page splashes, this means it can take two or three minutes just to read a couple of short sentences worth of script. It’s consistently been a roadblock for me getting into a lot of their comics, since they shoot for long-form stories that can be handily collected. The simple truth is that if I can read 24 pages of a comic book in 5 minutes, 4-6 months of non-Flash interface webcomics in 10 minutes or 30 1-5-panel pages in a half hour, I’m almost always going to to go with the first two options. It boils down to simple time and math, as well as the annoyance I feel spending more time watching the word balloon icon load (he’s basically the Microsoft Word paper-clip of the webcomics reading experience for me) than reading comics, which is what I want to do.

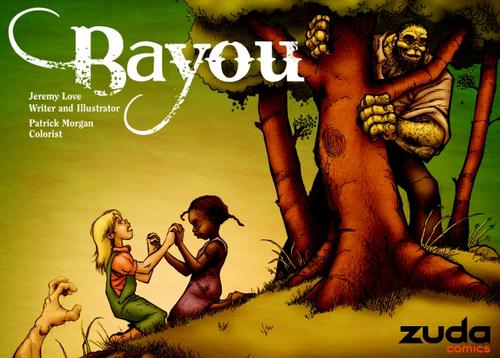

And Bayou by Jeremy Love is an instance where I really wish that wasn’t the case, because it features the best uses of magic realism in story telling that I’ve read in months. There’s a real sweet spot in truth-telling that comes from the gray area between folk stories and mythology where they bleed into real-world understandings. At a time when so many peoples’ politics and world views come from folk truisms and fragmented, re-contextualized religious teachings, this genre of story has been one of my favorites since I first encountered Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses and Neil Gaiman’s American Gods. Setting this tale in the American South taps into the region’s rich folk history that rose up from atrocious institutionalized practices and one culture’s de-humanization of another while the other was forced to raise children under that persecution. For me, this first volume from the series had in its aesthetic innocence all of the tension I felt the first time I heard Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” and a similar hellish carnival of coyly whimsical imagery to what deeply affected me the first time I read John Berryman’s The Dream Songs.

The coloring is lush and evocative of the Mississippi climate and environment of the real world, and the illustration is hauntingly cartoonish for its subject matter — similar to the way Gabriel Bá’s style works in B.P.R.D.. There are a lot of soft-penciled, sketchy moments, though, which tend to take me out of the moment in the same way a lot of Bill Sienkiewicz imitators shake me loose of from their unrefined moments in monthly comics. It wasn’t a consistent problem, though, so the biggest effect it had on my reading was sending me back to try to figure out if the style was trying to differentiate flashbacks from narratively current events. I don’t think that was the case, though.

The characters are brilliant. Most of them come across somewhere between Frank in Donnie Darko and the White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland. Their designs come from history, established folklore, and historical race-based caricature, which underscores the tenser moments with a simmering note of horror. It’s a beautiful piece of work.